Physical interpretation of the derivative

The primary concept of the calculus deals with the rate of change of one variable with respect to another

Instantaneous speed

Let’s imagine a person who travels 90km in 3 hours, his average speed (rate of change of distance with respect to time) is 30km/h, of course he doesn’t need to travel at that fixed speed, he may slow down/speed up at different times during the time he traveled, for many purposes it suffices to know the average speed.

However in many daily happenings the average speed is not a significant quantity, if a person traveling in an automobile strikes a tree the quantity that matters is the speed at the instant of collision (this quantity might determine if he survives or not)

| concept | description |

|---|---|

| interval | happens over a period of time |

| instant | happens so fast that no time elapses |

Calculating the average speed is simple, by definition it’s the rate of change of distance with respect to time

The same computation process can’t be applied to get the instantaneous speed at some point in time since instantaneous means that the event happened in an infinitesimal or very short space of time, then distance and the time might be both zero hence using the average speed definition won’t help because

We can’t compute it with the knowledge we have right now but we can surely approximate it, let’s say that there’s a ball dropped near the surface of the earth and we want to know its instantaneous speed after 4 seconds, to calculate the instantaneous speed at any point in time we need to know the distance it travels after some period of time, this relation could be expressed as a formula which relates distance and time traveled, the formula that relates the distance (in feet) with the time elapsed is

We can calculate the distance the ball traveled after 4 seconds by replacing

Let’s also compute the distance the ball traveled after 5 seconds

The average speed for this interval of time is then

So the average speed during the fifth second is

Let’s register more computations of the above process with smaller and smaller intervals of time in a table

|time elapsed after 4 seconds| 1| 0.1| 0.01| 0.001| 0.0001|

|average speed (in feet/s) |144|129.6|128.16|128.016|128.0016|

Of course no matter how small the interval is the result is not the instant speed at the instant

Method of increments

Let’s redo the process described above over an arbitrary interval of time, to do so let’s introduce a quantity

The formula for the example above is

When calculated once by the end of the fourth second is

When substituted with the interval

Where

The average speed in this interval of time is then

To compute the instantaneous speed the interval

Generalization

Let’s generalize the process above for

Subtracting

Dividing both sides by

Just like stated above to compute the instantaneous speed the interval

It has been customarily since the days of Euler use

It’s desirable to have some short notation for the statement that we have evaluated the limit of as the values of

Where lim is an abbreviation for limit, replacing

To some mathematicians this notation is somewhat lengthy, hence mathematicians replaced it with different variations

The rate of change is not always related with time or distances, a generalization of the formulas above is needed, instead of the symbols

Let’s calculate the instantaneous rate of change of

Subtracting

Dividing both sides by

The instantaneous rate of change of

We can also use the variations for the notation of the rate of change

What we did with the process above was to find the instantaneous rate of change of

Geometric interpretation of the derivative

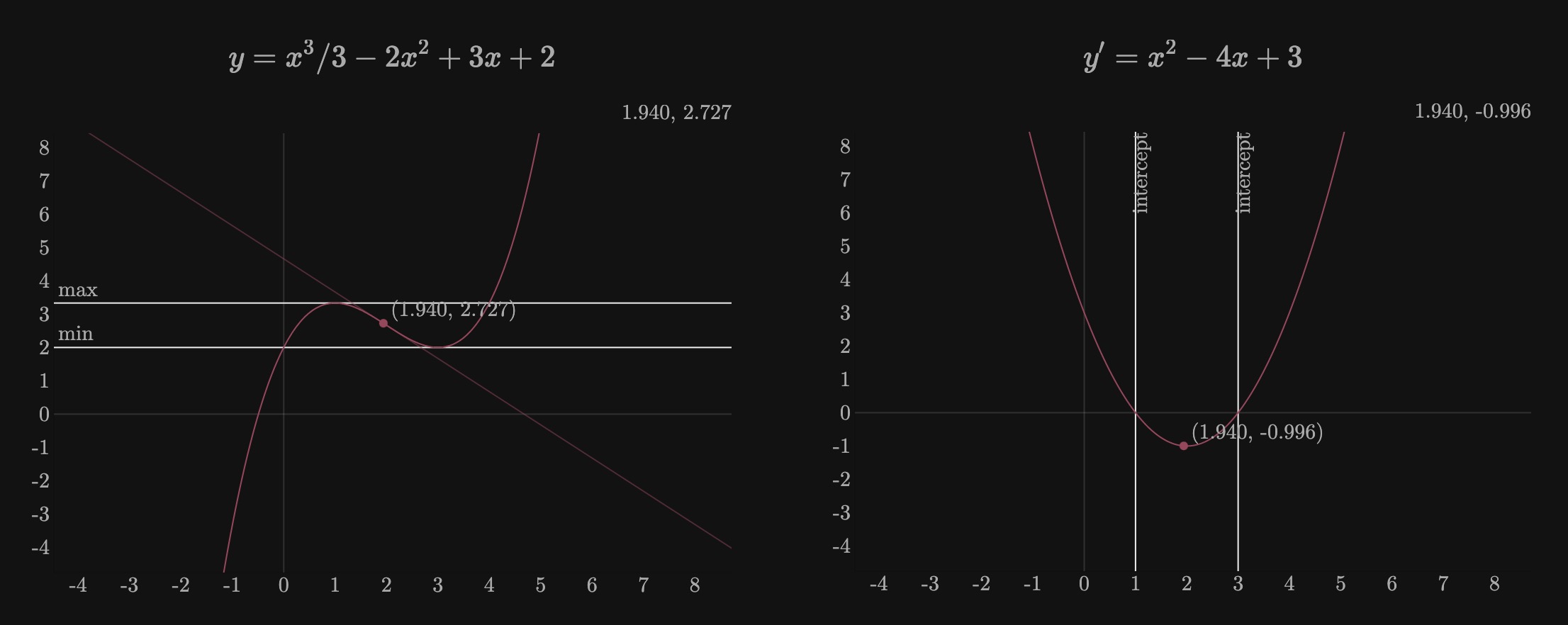

Let’s graph the following formula

A point belonging to this geometrical representation of

Let’s say that

The slope is a quantity that describes the direction and steepness of a line and is calculated by finding the ratio of the vertical change to the horizontal change between any distinct two points on the line, the previous statement expressed as a formula is

What if the movable point get closer and closer to the fixed point such that

Let’s find the instantaneous rate of change of this function evaluated at

This fixed number is the value of the slope of the line tangent to the derivative function when it’s evaluated with

Substituting

If we graph this line next to the geometric representation of

Before finding the equation of the slope for any value of

Now that we have an idea of the values of the slope let’s find the value of

By looking at the line we confirm our expectation of the values, any point which belongs to the line whose

There are infinite tangent lines to the curve that represents

Second Derivative

Going back to the falling object formula (

The instantaneous rate of change of the distance with respect to time is

Now

The instantaneous acceleration obtained above is the derived function of the isntantaneous speed which is the derived function of the distance function, then we can relate the instantaneous acceleration and the distance function with the following notation

The function above is called the second derived function of

The chain rule

Physical problems lead to more complicated algebraic functions, for example

If

Expressed in the function notation

Then

Returning to the original problem, let’s find the derivative of

Let

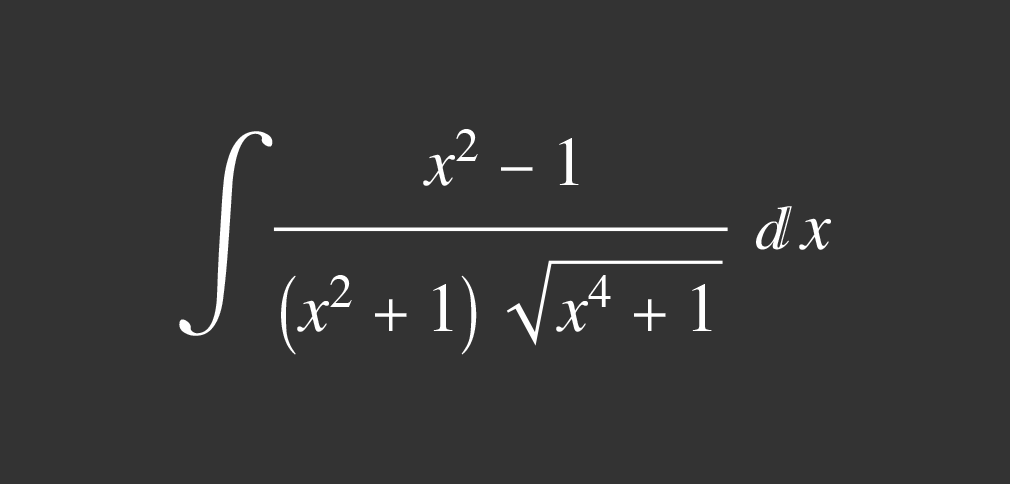

Differentiation of implicit functions

Going back to the definition of a function, it’s a relation between two variables such that given a value of one in some domain there’s a unique value determined for the second variable however functions often occur in forms where giving the independent variable some value will not result in a unique value, for example the equation of a circle of radius equal to 5 is:

Here

We know that

Applying a differentiation process to

Solving for

Theorems on differentiation

Read “Calculus: An Intuitive and Physical Approach”

Applications of the Derivative

- Determination of the velocity and acceleration of a particle given its distance as a function of time

- Concentrate light, sound and radio waves in a particular direction (see the reflective property of the parabola )

- Finding the maximum/minimum value of a function, i.e. find the largest/smallest value of

- Approximation of the roots of a polynomial with Newton’s method, described here

Maxima/minima

Let’s say that we throw an object into the air and we want to know the maximum height it acquires, as it rises it’s velocity decreases and when it reaches the highest point its velocity is zero, we also know that the velocity is the instantaneous rate of change of height with respect to time hence the derivative is involved in this process and therefore we expect it to be involved in other maxima/minima problems

More generally if

Let’s see an example, the following function has a maximum value of

Now the problem reduces to finding the points where

And we see that:

The process didn’t actually find the maximum/minimum values since for

Applications of maxima/minima

- refraction of light, we can build a function of time which relates the velocity/distance the light travels in different mediums, finding the derivative and making it equal to

- finding the sides of the rectangle with the maximum perimeter

Newton-Raphson method

The slope of the tangent line of a function

Newton find out that if we find the intercept of this tangent line with the

if

Solving for

Finding the square root of a number

Let’s say that we want to find the square root of a number

The function to use is then

whose derivative is

Substituting in

double square_root(double n) {

// initial guess

double EPS = 1e-15;

double x0 = 1;

while (true) {

double xi = (x0 + n / x0) / 2.0;

if (abs(x0 - xi) < EPS) {

break;

}

x0 = xi;

}

return x0;

}